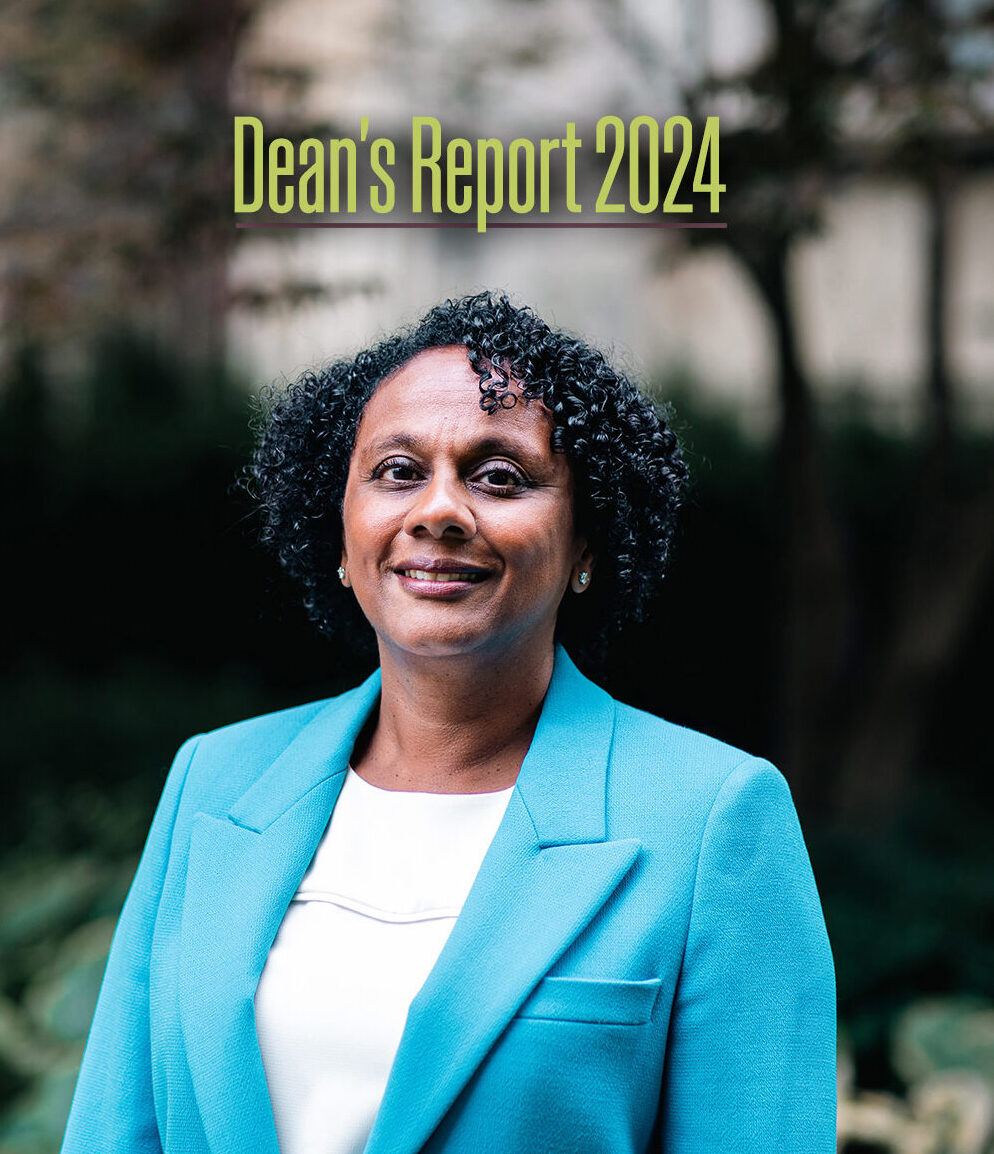

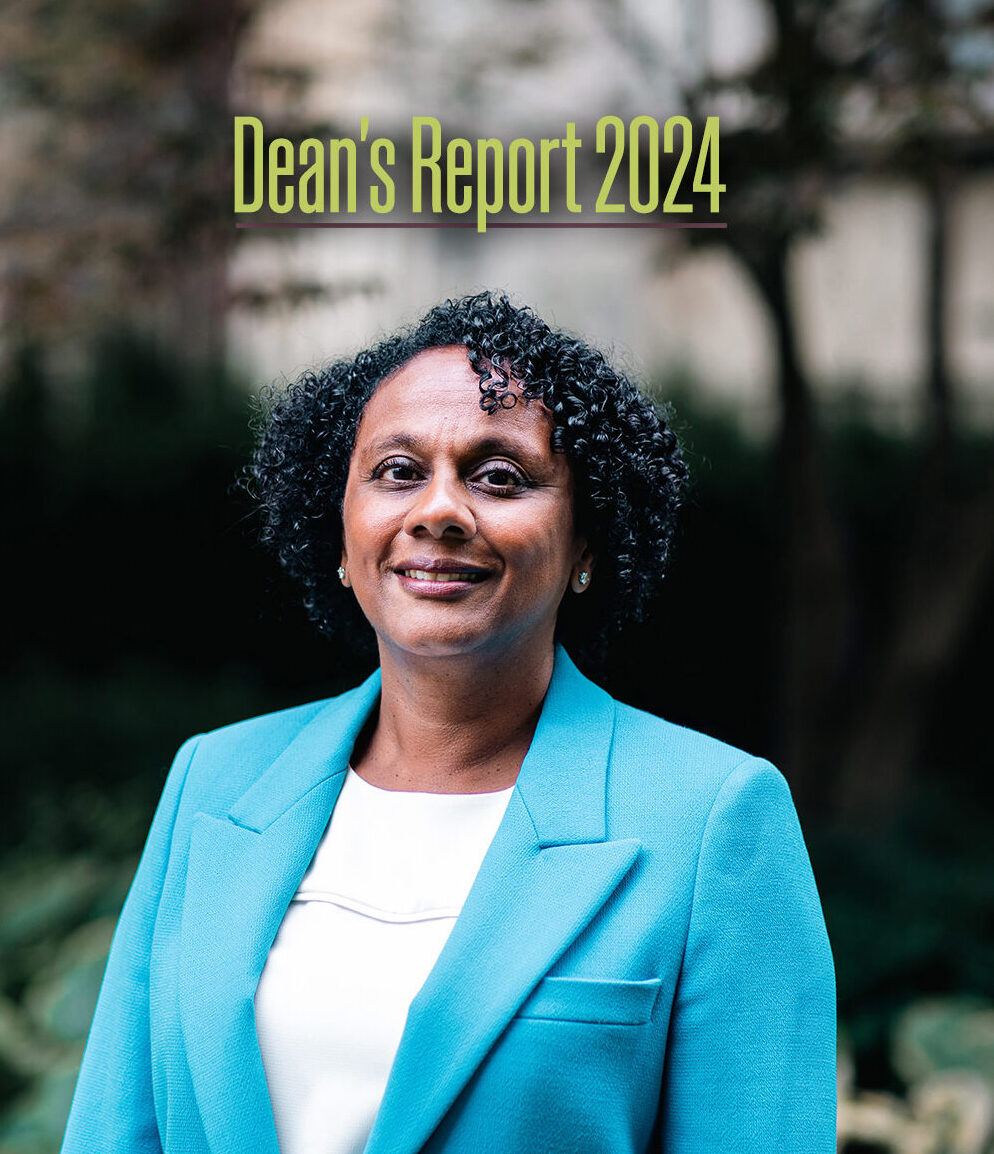

It is my pleasure to share with you the 2024 Dean’s Report for the Temerty Faculty of Medicine at the University of Toronto. The report is an overview of our activities in the last academic year, as Canada’s largest faculty of medicine and one of the most productive health sciences hubs in North America. Scroll through the report and you’ll find feature stories on our work and people, who are shaping the future of medicine and health care; a progress update on the goals of our academic strategic plan; and Vitals, with performance metrics including our global rankings, education enrolment and research output.

For those of you who don’t know me, let me introduce myself. I began my term as dean of Temerty Medicine and vice provost, relations with health-care institutions in July — after eight years of outstanding leadership from Professors Trevor Young and Patricia Houston, as dean and interim dean, respectively. I am a graduate of our medical school, a paediatric nephrologist, and a discovery and translational researcher with a focus on kidney disease and transplant. I am a clinician-scientist at The Hospital for Sick Children, and have served as vice dean of strategy and operations and co-chair of the finance committee at Temerty Medicine. I have also been privileged to hold leadership roles with the Society for Pediatric Research and the American Pediatric Society.

For those who do know me, you’ll know that my approach to leadership is collaborative, data-driven and people-focused. I have met with many faculty, learners, staff, alumni and donors in the past few months, and learned about your concerns, achievements and hopes for the future. We clearly face challenges as a Faculty, from the ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, to fiscal pressures and the growing complexity of health care and medical science. But I am moved by the ideas and passion that many of you bring to solve these and other problems every day, across our departments and partner institutions. And I am excited by what more we can do to realize our research potential and empower our people.

In the coming year, we will begin a strategic planning process to set new goals, building on our existing academic plan. Work is already underway on several priorities, many identified by you in consultation with our leadership teams. These include solidifying and expanding our clinician-scientist training programs; supporting and harmonizing career development for graduate students across our life sciences departments; and better recognizing the effort and expertise of our faculty members, in a wide range of clinical and research sites. We also continue to plan for construction of the James and Louise Temerty Building on the current site of the Medical Sciences Building’s west wing, and to develop better performance metrics to track progress on key goals, relative to peer institutions.

I look forward to advancing these and other priorities, and to meeting many more of you across our Temerty Medicine community this fall.

Lisa Robinson, MD, FRCPC, FCAHS

Dean, Temery Faculty of Medicine

Vice Provost, Relations with Health-Care Institutions, University of Toronto

Professor Neil Goldenberg

By Jim Oldfield

Coming to Toronto as a life-sciences student was life-changing for Neil Goldenberg.

It was 2001. Goldenberg had just finished his third year of undergraduate study in British Columbia, and had come to the University of Toronto for a summer research program at the Institute of Medical Science.

By chance he landed in the lab of Mel Silverman, a physician and researcher at University Health Network who was also founding director of U of T’s MD/PhD Program, launched in 1984.

“Like many undergrads, I was unaware that clinician-scientist training existed,” says Goldenberg, now an associate professor of anesthesiology and pain medicine at Temerty Medicine, and a scientist and staff anesthesiologist at The Hospital for Sick Children.

“Suddenly this whole other path of the clinician-scientist became apparent, and it was very attractive.”

Clinician-scientists embody the potential of modern medicine, in many ways. They draw relevant questions from the clinic, test them in the lab and in trials, and can bring treatments back to patients.

They also create an essential bridge for basic scientists, who make fundamental discoveries but often cannot translate their findings to patients.

And, they have been central to amazing medical advances, from insulin and vaccines to organ transplants and gene therapies.

But in Canada, the pipeline for clinician-scientist training is at risk.

“Funding for MD/PhD programs in particular is a major challenge,” says Nicola Jones, director of the Integrated Physician Scientist Training Program at Temerty Medicine, who is also a senior scientist and gastroenterologist at SickKids.

When the Canadian Institutes of Health Research cut funding for those programs in 2015, Jones says, U of T was able to close the gap through donations. But that recent support is not stable, and has not allowed the university to expand the program.

Temerty Medicine will welcome nine new MD/PhD students this year, and the school boasts the largest program of its kind in Canada. But many smaller U.S. schools have the same number of students, and Harvard’s program is about three times larger.

As well, student interest in MD/PhD programs has plateaued, as reports on these programs have repeatedly found — including one by U of T’s Task Force on Physician Scientist Education in 2012. That report noted the length of training, which runs eight years and often more, as just one of several disincentives.

Jones points to additional trainee concerns today, such as cost of living in Toronto, growing clinical demands (especially in Toronto, which draws complex patients), and a struggling health care system heavy with administrative and technological burdens.

“And there has always been a huge push in Toronto to ensure that clinical training and care aren’t comprised by research time, and vice-versa,” Jones says. “That tension is always there.”

Jones and her colleagues are working to address these challenges.

They have shored up different on-ramps for medical students to experience research, such as the summer research program and a 20-month graduate diploma in health research, and prioritized the Clinician Investigator Program, so residents can pursue graduate- and postgraduate-level research.

They are also developing an accelerated pathway for MD/PhD graduates, with a competency-based approach to residency training that provides more time for research. Four clinical departments plan to pilot this pathway, which Jones says should limit the number of Canadian students who seek this option in the U.S.

And this fall, they will pilot a mentorship program that pairs clinician-scientist trainees with early career researchers and other physicians, in small groups. Jones says the structure is based on feedback from a soon-to-publish national survey of trainees and alumni, and learnings from the business world.

Goldenberg, who says he has benefited greatly as a mentee and mentor throughout his career, likes the new program. “Mentorship is unbelievably important, for practical and psychological reasons. But people need a panel of mentors with different experiences, at work and in life. This program should enable that through formal and more organic connections.”

Making connections, between similar and disparate people and ideas, defines success for many clinician-scientists. But for Goldenberg, who is the John Alchin and Hal Marryatt Early Career Professor in Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, training as a clinician-scientist also brings intrinsic rewards.

“I loved most of my training, largely because learning from outstanding people really resonated with me,” he says. “Just find excellent people, and learn to be the best as a clinician and researcher. There’s tremendous value in that.”

Professor Nana Lee (left) doctoral student David Van Ommen (right)

By Betty Zou

According to the 10,000 PhDs Project, an initiative of the School of Graduate Studies at the University of Toronto, the number of PhD graduates in the life sciences more than doubled between 2000 and 2015.

At the same time, the number of openings in the academic job market did not keep pace — only one in five life sciences PhD graduates ended up in a tenure stream position — so where did all the PhDs go?

As the U of T data show, graduates with a doctoral degree increasingly found employment in the private, public and charitable sectors, where their technical expertise, creative and critical thinking skills now help drive the innovation economy in Canada and beyond.

More recent data show this trend continues, along with an uptick in the number of life sciences graduates landing tenure-stream jobs. But how smoothly students find their way into the growing variety of possible careers is another question entirely.

Like many of his peers, David Van Ommen started graduate school at Temerty Medicine with the vague notion that he wanted to find a job in industry. After his undergraduate studies at U of T, he worked for a year as a research technician.

“I realized that I needed a master’s or a PhD to get a job that pays well and would let me grow in industry,” says Van Ommen, who is a third-year PhD student in the department of biochemistry.

As co-chair of the biochemistry graduate student union this past year, Van Ommen and his fellow co-chair Tina Qiu spearheaded the creation of a new industry professional meet-and-greet series. The pilot event featured a speaker who works at AstraZeneca Canada and included a talk as well as small group meetings for graduate students and postdoctoral fellows to connect with the speaker.

“It was very popular, so we’re hoping to expand it and invite someone once a month,” says Van Ommen. He’s also planning to broaden the careers profiled to include areas such as law and consulting.

The student union also helps to organize the annual Benjamin Schachter Memorial Lecture, which brings in biochemistry alumni to share their post-PhD career journeys.

Van Ommen notes that while most faculty members are supportive of their graduate students’ interests in pursuing careers outside academia, they may not have the connections in those sectors to facilitate introductions for their students. That’s why events like the Schachter Memorial Lecture and industry meet-and-greet series are so helpful.

“Networking is important and it’s probably the easiest way to get hired,” says Van Ommen. “These events introduce students to people in the industries they want to join so that they’re not on their own trying to find and make connections.”

The importance and how-to of networking are also topics that are covered in the department of biochemistry’s graduate professional development course. First rolled out in 2012, the course was developed by Nana Lee, a professor in the teaching stream and director of graduate professional development and mentorship at Temerty Medicine and Reinhart Reithmeier, emeritus professor of biochemistry.

The course aims to provide students with the information, network and tools they need to succeed in the competitive academic and non-academic job market. It also includes a session to network with alumni and empowers students in creating their own preferred career pathway. Unlike other career development resources, which may not always be tailored to students in the life sciences, the GPD course leverages Lee’s experiences as a life sciences PhD graduate who has worked in both academia and industry.

“The course has helped a lot of people in this department figure out what they want to do and then get a job in that career path,” says Van Ommen.

How to help more graduate students prepare for and navigate their post-PhD journeys is something that Lea Harrington thinks about a lot. As professor and chair of the biochemistry department, she has championed the student union’s efforts to expand their industry meet-and-greet event series, and says she is keen to build on the department’s history of supporting career development.

“Our faculty and learners have been real drivers of career advancement, and we have also learned from other departments and academic environments leading the way in these areas,” says Harrington. “We strive to share and expand the resources available that ensure our graduates can fully explore the new opportunities that life sciences training affords them.”

By Jim Oldfield

Marissa Joseph needed a nudge toward academic promotion.

As a full-time clinician-teacher with an interest in health equity and a young family at home, Joseph felt the application process for the rank of associate professor would not be worth it.

“I didn’t see the value in it, and didn’t need the recognition. It just seemed like one more onerous thing to do,” says Joseph, who was then an assistant professor of dermatology at Temerty Medicine, a medical director at Women’s College Hospital and a staff physician at The Hospital for Sick Children.

But after encouragement from her colleagues and division director in the department of medicine, Joseph applied and was promoted this spring.

“I’m glad I went through the process,” she says. “I was able to see what I’ve done more clearly, and to recognize that as a racialized woman, promotion improves representation and diversity. It sets an example for learners and enriches education.”

Senior promotions, which include the rank of associate and full professor, can also bring tangible benefits — such as increased responsibility and job opportunities. But medical schools have long struggled to apply promotions criteria that fairly reflect the variety and impact of academic work.

“Historically, the work of some faculty members has been more easily valued and captured than others,” says Upton Allen, chair of the decanal promotions committee and a professor of paediatrics at Temerty Medicine.

“Research metrics such as grants and high-impact publications are visible indicators, in contrast to clinical teaching and other activities, which are harder to define and quantify,” he says.

Clinical teaching involves many hours of preparation for lectures, but also small-group and individual interaction, during clinic and off-hours.

Other relevant work includes publications in books and other media, advising on clinical guidelines, and public speaking or outreach, to name just some. It falls under the category of creative professional activity, or CPA.

Allen will lead an implementation team to build on recent updates to the criteria for senior promotions.

One priority for the team will be better incorporation of equity, diversity, inclusion, Indigeneity and accessibility (EDIIA) into different promotion platforms, Allen says.

Guidance on how to include EDIIA varies across departments, and the decanal promotions committee needs clearer criteria to assess it, Allen says.

In the past year, CPA was a factor in 64 per cent of Temerty Medicine promotions, and only 12 per cent of successful applications included statements on EDIIA, which were optional.

Joseph, who went forward on the platform of ‘excellence in teaching and education, and competence in CPA,’ has engaged in a range of equity work — including mentorship, community collaboration on skin of colour, and as divisional EDI lead.

But she says including that work in her application was not an intuitive process.

Allen says other focus areas for the implementation team will include helping faculty better define CPA questions and answers before diving into that work; making better use of information technology to track CPA, teaching and research; and streamlining the senior promotions manual.

Meanwhile, a working group is looking at how academic appointments and promotions can better recognize more faculty members — including part-time and community-based clinician-teachers, and full-time researchers.

Lynn Wilson is a co-chair of that group, and vice dean of clinical and faculty affairs at Temerty Medicine. She says that while the Faculty and some departments do acknowledge faculty members through events, funding and awards, more can be done.

As well, different faculty appointments determine access to a tuition waiver and a scholarship program for dependents. The working group, co-chaired by Professor Alison Freeland, is reviewing ways to provide further supports to faculty without those benefits.

“All faculty members belong here,” Wilson says. “Many are great teachers or have found innovative ways to improve care, and some do research. We need to recognize their contributions in tangible ways.”

For Joseph, senior promotion has opened new opportunities. But she says the intangible benefits of academic work bring the most reward, especially with clinical teaching.

“Sometimes it’s little nuggets of feedback that make it worthwhile,” she says, whether as teacher evaluations, interactions with colleagues — or comments from patients.

“I talked about the need to ask before touching recently, in front a patient and trainee,” Joseph says. “I know this as a dermatologist, but also as a Black woman, because touching afro-textured hair uninvited can seem like an act of violence.”

The patient thanked her profusely and said she was very uncomfortable removing her hair piece.

“Caring for patients is a privilege, but it’s also difficult and at times demoralizing,” Joseph says. “Knowing that a trainee’s future interaction with a patient might be safer is meaningful. Often, it’s what keeps me going.”

Three key papers from Temerty Medicine researchers in 2023–24

Researchers at Temerty Medicine and our affiliated hospitals are among the most productive in the world. In the fall of 2023, the Toronto Academic Health Science Network released a report that offered unprecedented insight into that productivity, relative to peer life science hubs in North America.

Among the report’s findings, University of Toronto and affiliated scientists published over 63,000 life science papers from 2018 to 2022 — second only to Harvard University and its affiliates and well ahead of Johns Hopkins University and the University of California San Francisco.

The quality and scope of our research is deep and wide, placing us second during the same four-year period in most-cited (top 10 per cent) papers across life science, preclinical and clinical studies at peer research hubs.

Here we spotlight three research groups who published high-impact papers in the past year, which advance our understanding of biology, medicine and health care — and point toward a future with less disease and better health.

Researchers uncover human DNA repair by nuclear metamorphosis

Professors Karim Mekhail and Razqallah Hakem and colleagues discovered a repair mechanism in human cells that fixes DNA double-strand breaks, a serious type of genetic damage that plays a role in many diseases.

The elegant process involves a network of filaments that forms in the cytoplasm around a cell’s nucleus, prompting the formation of microtubules that press into the nucleus and capture the double-strand breaks inside it, ferrying them back to the nuclear membrane for repair.

The findings in part explain how human cells remain healthy, and suggest new approaches to triple negative breast and other cancers, as well as premature aging.

Study identifies new roles for glucagon-like peptide-1 in the brain

University Professor Daniel Drucker and his team discovered a gut-brain-immune network that controls inflammation across the body and in turn influences organ health.

The researchers found that glucagon-like peptide-1 (known as GLP-1) receptor activators reduce systemic inflammation, even in organs with few receptors for this gut hormone, but only when GLP-1 receptors in the brain were left unblocked.

The intriguing findings open new lines of research into which brain cells interact with GLP-1 and the types of disease-related inflammation they may mediate.

Quitting smoking at any age brings big health benefits, fast

Professor Prabhat Jha and colleagues found people who quit smoking see major gains in life expectancy much more quickly than was previously known.

The study, which looked at 1.5 million adults over 15 years, shows that smokers who quit smoking before age 40 can expect to live almost as long as those who never smoked. Those who quit at any age return close to never-smoker survival 10 years after quitting, and about half that benefit occurs within just three years.

The study highlights the importance of government tax policy on cigarettes, and the value of cessation supports such as clinical guidelines and physician advice.

Temerty Medicine’s Academic Strategic Plan, approved in 2018 after widespread input from across the Faculty, remains a guide and inspiration for our faculty members, learners, graduates, staff and partners.

The plan includes three strategic domains of focus and two enabling elements, which together drive our vision to be an unparalleled force for new knowledge, better health and equity.

We continued to make progress on that vision in the past year, across all five plan domains and enablers.

Ecosystem of Collaboration

The Canadian Hub for Health Intelligence and Innovation in Infectious Diseases, co-led by Professors Jennifer Gommerman and Scott Gray-Owen, received $72 million in federal funding to boost Canada’s biomanufacturing capacity and readiness to respond to emerging health threats.

The University of Toronto and the CAMH also received over $6 million from the non-profit organization Mitacs and industry partners, to advance and commercialize radiopharmaceutical technologies. The funds will set up a national hub for research translation and training co-anchored by Temerty Medicine, for applications in cancer, neuropsychiatry and cardiovascular care.

Within the university, we launched a new academic centre with three other health faculties to help address global ecological changes, through more sustainable health systems and a focus on planetary health.

Other collaborative efforts in the last year included:

- A new partnership with community affiliate Georgian Bay General Hospital, aimed at increased recruitment and retention of clinical staff, and an expanded scope of services at the hospital.

- The national launch of a new course on Black health and anti-Black racism for medical and health learners, faculty and practitioners, to address disparities in Canadian health care and patient outcomes — in partnership with the Dalla Lana School of Health and Dalhousie University.

Groundbreaking Imagination

We continued to prioritize financial support for graduate learners, to offset tuition fees and cost of living in and around Toronto. This work included updates to the Temerty Medicine harmonized base funding agreement, top-up funds for stipends, fellowships and awards, and fundraising for student endowments.

We also expanded support for graduate student career development and entrepreneurship, in particular by partnering with Lab2Market, to help learners turn their ideas into successful companies. These efforts complement our continuing focus on professional master’s programs in laboratory medicine, medical physiology and more.

To ensure our students continue to train in the best research facilities, we secured $10 million in funding for upgrades to the Toronto High Containment Facility. This space enables research on SARS-CoV-2, mpox and other high-risk pathogens, and is a critical resource for researchers across Ontario and Canada.

Other work to enable groundbreaking imagination included:

- Contributions to a finalized list of research metrics that all TAHSN partners will collect annually to demonstrate collective research impact across the network.

- A new ethics seminar for second-year MD Program students on professional values and responsibilities, bias, and building trust in the physician-patient relationship.

Excellence Through Equity

Excellence through equity remained a key theme in work across Temerty Medicine departments and divisions the past year. At the Faculty level, we focused delivery of educational programming and events, development of infrastructure, and strategic planning across the areas of equity, diversity, inclusion, Indigeneity and accessibility.

Office of Inclusion and Diversity

- Held equity-related workshops on psychological safety and conflict resolution with the Centre for Faculty Development and other partners; developed new resources such as a guide to inclusive educational events and a biweekly newsletter; and continued to curate existing online resources.

- Led learner support and outreach initiatives such as the Diversity Mentorship Program (which included a pilot with our rehabilitation sciences sector); co-led an environmental scan on mentorship opportunities and advised on a mentorship strategy for medical learners; and re-launched the EDI action fund for learners, with an updated guideline and application process.

Office of Indigenous Health

- Began a pilot collaboration with the Learner Experience Unit to ensure access to a full range of supports for any Indigenous learner who experiences mistreatment.

- Sponsored Indigenous medical students to attend the Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada annual mentorship gathering and meeting in Winnipeg.

Office of Access and Outreach

- Reached 3,000 high-school, undergraduate and graduate students through several programs in the last year, a 50 per cent increase from 2022-23; held over 40 events and worked with over 30 departmental and community partners; and celebrated the 30th anniversary of the Summer Mentorship Program.

- Janelle Hinds joined the team as special projects officer, and will develop application pathway programs across the Faculty for Black and Indigenous students. Professor Andrea Boggild, a clinician-scientist at University Health Network, joined the office and leads the Mentor 2 Mentor program to help researchers foster inclusive learning.

Support Health & Wellbeing in Everything We Do

Through the Office of Learner Affairs, we continued to strengthen our many supports for learners across the medical education continuum, including skills enhancement, personal and career counselling, accommodations, mentorship and more.

We continued to refine confidential pathways to discuss, disclose or report learner mistreatment, and we updated our Learner Experience Unit electronic case management system to enable more detailed and nuanced analysis of mistreatment disclosures and reports.

We also continued to prioritize the wellness of faculty members, and created ‘leading for wellness communities of practice,’ which train and support faculty leaders to enable the wellness of health care workers. More than 75 faculty members participated in a year-long course of group support and knowledge-sharing, aimed at addressing chronic burnout in front-line staff.

Infrastructure, Policies & Technology that Compel Collaboration & Support Sustainability

Our information technology unit, MedIT, worked to provide secure, reliable and robust infrastructure after launching last year, through evolving financial and service models that help reduce costs and increase quality.

The rehabilitation sciences sector, working with the Office of the Chief Administrative Officer, undertook a review of its financial and service delivery model aimed at creation of an administrative hub that will provide sector-wide and sustainable support.

We also worked to improve our understanding and use of data, and will launch a data community of practice this year that will focus on data literacy, collaboration, and standardizing practices.